Common Design Mistakes are costing the construction industry far more than most people realise.

I read recently that rework is currently eroding contractor profit margins by up to 30% and increasing the likelihood of injury by 70%. A separate study suggested 12% of all Australian construction work is rework.

Is it because we love building things that we want to do it twice? Or because we’ve made a good margin on a job and want to “give back”? Of course not!

It’s because we make mistakes. “To err is human” is indeed a fact, but not an excuse. We all strive to produce the best design, the most successful project, an awe-inspiring marvel. But there’s often a hitch. Something that gets in the way of the pursuit of perfection.

These are the seven deadly sins of design.

1. Rushing projects

Solution:

Make sure you have a well-organised work schedule, don’t take on too much and plan the process of each design carefully before starting.

2. Poor attention to detail

Common Design Mistakes often hide in the details.

The devil is in the detail. You need to be able to focus on the design for long periods, and also get into the habit of coming back fresh to your design after a break and checking it over with a fine-tooth comb. A design is as good as its weakest part, so all aspects, down to the bolts and the welds, need to be considered. Relying on a checker to catch the flaws in your design is where it can go awry.

Solution:

Be meticulous. Assume you don’t have a checker, and that the next step is construction.

3. Getting the dimensions wrong

Getting The Dimensions Wrong is one of the most frequent Common Design Mistakes.

A dimension on a CAD drawing is rarely “wrong” because it is automatically dimensionally correct, but that can be misleading. The entire assembly could still be ,the wrong size.

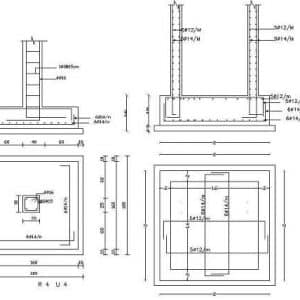

It is at the interface between different parts of the design where errors creep in, for example, footing centres not matching column centres, or equipment support beams in the wrong position. These are classic examples of Common Design Mistakes that can cause costly rework.

Solution:

Check your dimensions. In fact, don’t just check them, double or triple check them, then get someone else to check them.

4. Falling behind the curve

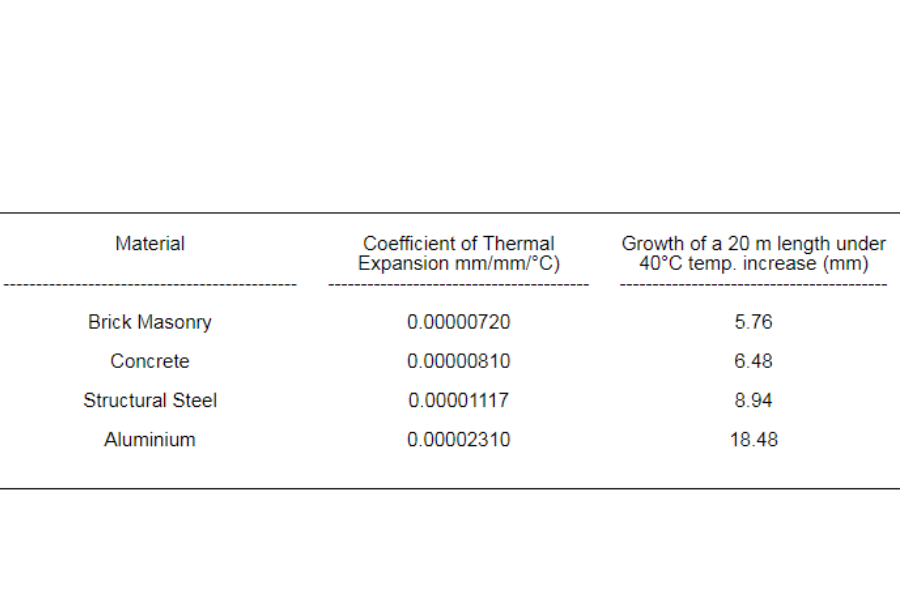

The construction industry is often slow to adopt new technology, but change is happening. Methods, materials, and standards are constantly evolving, and it is essential to stay ahead of the curve. Falling behind can lead to inefficiencies, outdated designs, and compliance issues; frequent sources of Common Design Mistakes.

Staying current is not just about using the latest software or following trends. It means understanding emerging materials, construction methods, and regulatory requirements, and applying that knowledge consistently in every design. Teams that fail to do this risk repeating errors that could have been avoided, wasting time, money, and resources.

Solution:

Don’t get left behind. Update standards, subscribe to industry journals & publications, and be a member of your relevant industry bodies.

5. Not thinking about the assembly process

It’s easy to get wrapped up in your design and forget about the practicality of actually putting it together.

One of the most overlooked Common Design Mistakes is not considering misassembly during the design phase. Make sure you are thinking ahead and trying to foolproof your design. In other words, wherever possible, design the pieces so they can only go together in the correct way, reducing the chance of errors during assembly and avoiding costly rework.

Solution:

Visualise the construction process. From the parts to the whole, simulate the construction, looking for problems with fit, access, safety, and then revise the design to suit.

6. Not applying common sense checks

Solution:

Make sure gross errors in the calcs are fixed by performing “sanity checks” on the inputs and outputs. Consider quick hand-calc checks, look at global reactions, deflection plots, and always question the results of analyses.

7. No consideration of design presentation

At the end of the day, your design is going to be seen by lots of people – checkers, engineering managers, clients, etc. It needs to be clear, not just to you, but to everyone else.

Solution:

Prepare clear documented reports of the design as it unfolds. State the assumptions, and review each of them at the end of the design – convert assumptions into fact wherever possible. Consider that somebody will need to follow them, so present your calcs with clear references to methods, codes etc. Expect scrutiny and ensure any questions are answered in the report.

Conclusion

Some of these “sins” seem pretty obvious, but it’s the obvious that catches us out much of the time. If you were designing a rocket, and you’ve never done it before, you’d likely make less mistakes than the NASA design team because of the extra care and diligence you’d bring to the project.

We use an effective overall strategy to reduce rework and minimise error at Yenem whilst maintaining care and diligence on all projects. It involves systemised workflows, automated repetitive tasks and above all else, open and clear communication within the team and all stakeholders to collaborate ideas and increase the likelihood of project success.

Can we help you to reduce rework, increase your profit margin and impress your clients? Let’s meet for a coffee and chat.